How these cities became rat-free zones

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt’s a stinky job but somebody’s got to do it – enter the rat detectives.

“If it weren’t for rats, I wouldn’t have had a job,” says Phil Merrill, head of the rat control programme in the Canadian province of Alberta. “I don’t like them, but I don’t hate them. I respect them. They’re adaptable little critters. And they’re challenging.”

In many ways brown rats, also known as Norway rats, are remarkable. They are fantastically prolific breeders, with quick gestation periods and big litters of babies. They eat almost anything – domestic rubbish, rotting meat, grain – and live everywhere people live. They can chew through metal, swim long distances, survive 50ft (15m) falls, emerge from your toilet and, it turns out, feel empathy.

Originally native to northern China, these rats have spread across every continent except Antarctica. As numerous other species decline, rats appear to be thriving – most obviously in our cities. They’re seen as one of the world’s most invasive species, harming native wildlife populations, damaging property, contaminating foodstuffs and transmitting diseases.

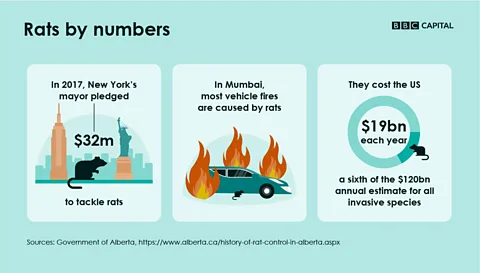

They cost the US $19bn each year, a sixth of the $120bn annual estimate for all invasive species. In 2017, New York’s mayor pledged $32m to tackle rats; in Mumbai, most vehicle fires are caused by rats. And while the urban myth that you’re never more than 6ft from a rat may not hold up, you’re probably not too far from one right now.

Except if you are in Alberta. Home to the cities of Calgary and Edmonton, and with a population of about 4.3m, Alberta is famous for oil, national parks and ice hockey. But it also has a lesser-known claim to fame: it’s the only part of the world with significant urban and rural populations that does not have a breeding rat problem.

So how did an area the size of Texas achieve a feat unparalleled anywhere in the world? Was it luck or the result of strategic genius? And what’s Alberta gained from keeping rats out?

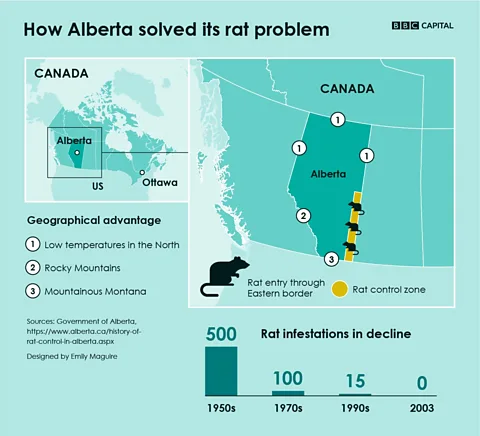

Pinch and zoom on mobile to expand

‘Kill At Sight!’

“We really have a geographical advantage,” says Merrill. “We started before we had rats – the rats came to our eastern border in about 1950 – and we said we don’t want rats, so we checked all the farms along the border where they were and poisoned them out. And we just don’t allow any more rats to come in.”

Geography certainly played a role – for a large area, there are few potential entry zones. Rats can’t survive the cold of the north or in the Rocky Mountains to the west. The southern border with Montana is mountainous and too sparsely populated for rats to spread.

That leaves defence of the eastern border. Rats arrived on the east coast of North America in the late 18th Century and slowly spread west, reaching neighbouring Saskatchewan in the 1920s.

“We’re not any smarter than Saskatchewan,” says Merrill. “The rats got to them about 30 years before us. The [provincial] governments at the time weren’t very developed – Saskatchewan wasn’t ready for them. By the time they hit our border, we had a department of health and a department of agriculture, and we had a system ready that we could actually do something.”

And they did. Rats were declared a pest in 1950, making rat control mandatory. Poison was used to kill rats that had made it into Alberta and to treat buildings that might shelter them in a strip 300km long and 20-50km wide along the eastern border. A rat control zone was established (it remains in place today) and pest control officers (PCOs) appointed to police it.

In parallel, a public education drive began. Most Albertans had never seen a Norway rat, so the government launched a campaign to help residents distinguish them from native rodents, sending out thousands of posters.

“They’re very effective visually,” says Lianne McTavish, a professor of art history, design and visual culture at the University of Alberta, who examined themes running through the posters. “They really focused on the tail… they wanted people to focus on the Norway rat, not other kinds.”

The posters, with emotive slogans like ‘Kill Rats At Sight!’ and ‘He’s A Menace To Health, Home, Industry!’, cast the rats as invaders and leaned heavily on war-time rhetoric, says McTavish. Another theme was good farmer, who kept a tidy homestead, versus bad farmer, who was sloppy and endangered his neighbours.

“At that time there were loads of campaigns – coyotes, grasshoppers – but the rat one, really people could get behind it and the government put money behind it and sustained it,” she says. “It was emotional too – ‘they are an invader, they are dangerous’. They could lobby people’s emotions and irrational fears with rats in a way they couldn’t with other things.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesRubbish dump detective

In the 1950s, there were over 500 reported Norway rat infestations in the rat control zone each year, but a decade later that number had dropped significantly. By the 1970s, says Merrill, there were about 50 each year, then 10-20 in the 1990s. In 2003, for the first time, the number was zero.

Today, the zone is routinely inspected, and infestations are dealt with efficiently (between one and three annually is the norm). Farms closest to the border are checked twice a year and adjacent sites once. It sounds like a lot, says Merrill, but the modernisation of farming – more steel granaries, for example – means rats have less access to food.

“We check feed lots, silage pits, wooden granaries,” says Merrill. “If we drive by a guy’s place and he’s got all steel granaries, we might stop and say hi, but it doesn’t take long. [The PCOs] can do 25-30 sites per day.”

Farmers are encouraged to maintain preventative bait stations, using warfarin, an anticoagulant. There are more efficient poisons, Merrill says, but warfarin has less impact on other wildlife due because it stays in the rat’s system for less time – it has a shorter biological half-life. (This makes it less likely that predators like hawks who eat rats will consume enough poison to be affected.)

When infestations occur, most people welcome help. “Some are a little reluctant – they have rats and they don’t want people to know – but most people just want to get rid of them,” he says. “We go back every week until we’ve cleaned it out.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThere’s also the job of investigating sightings that come in via a dedicated phone hotline. Most are cases of mistaken identity – often native muskrats - but rats do come in.

The morning I met Merrill, a man had trapped a rat near Innisfail, west of the control zone. It was in a garage he shared with a neighbour who had just returned from British Columbia; the rat had hitched a ride in his vehicle. “That’s a common thing,” says Merrill. “We get about two each month that’s a confirmed rat.” His advice – put out another trap to check for a companion. “When rats come in singly, it’s not that big a deal.”

It’s not always that simple, however. Sometimes Merrill must turn detective, like at the rubbish dump in the city of Medicine Hat in August 2012. “We had 21 single rats in the farms around it and 18 in the city. We knew it meant an infestation, but we couldn’t find it. We went to the dump six times – dumps are really hard to find rats in because of garbage blowing everywhere. Finally one of the PCOs found them at night.”

The infestation made national headlines and even some international ones questioning Alberta’s rat-free status. By October it had been controlled and the nest destroyed. The body count, Merrill believes, was at least 300. As to the source, it’s thought the rats arrived in hay left in farm machinery that had been brought into Alberta for recycling.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesCounting the cost

Merrill, 67, has been in pest control since 1970. He’s quick to point out changes that make his job easier, like more modern farm buildings and control work in Saskatchewan, where infestation rates are falling. There’s also support from each municipal area in Alberta, which designates one officer to help with rat control when needed.

The rat control programme itself costs less than C$500,000 (US$372,000) annually, covering salaries for Merrill, six rat control zone officers and bait. It seems like a wise investment; back in 2004, the Alberta Research Council (ARC) estimated that the annual cost of having rats would be C$42.5m (US$31.6m).

Its figures were partly based on a US study which assumed that each adult rat consumed or destroyed grain or other materials valued at US$15 per year. That included fires caused by rats gnawing at wiring, polluted foodstuffs and losses linked to disease. The ARC estimated that if each farm had 20 rats and each household one rat, then the rat population of Alberta would be 2.1m.

Larry Roy, who co-wrote the ARC report, says he thinks it was “a very good, believable estimate at that time”. Estimating the economic impact of invasive species like rats is difficult, he says, and getting more exact data would require costly survey work. “If you’re in the general magnitude area, then that’s quite reasonable,” he says. “There’s no doubt in my mind that the programme saves millions and millions of dollars in rat control every year.”

Pinch and zoom on mobile to expand

Delinda Ryerson, executive director of the Alberta Invasive Species Council, believes the estimate “is within the ballpark but may be conservative”. It’s hard to put a value on, for example, the potential impact on native wildlife – like Alberta’s ground-nesting birds, whose eggs would be vulnerable to rats.

When it comes to health, there’s not enough information to assess what being rat-free has meant to Alberta, says Kaylee Byers, a PhD candidate at the University of British Columbia studying health risks posed by urban rats. “There is really no estimate or approximation of the impact of rats on the health of Canadians, and that’s largely because we haven’t any data on it,” she says. Byers is working with the Vancouver Rat Project, which is trying to close this knowledge gap.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesLearning Alberta’s lessons

Could Alberta’s experience help the wider world? Today’s rat control projects mostly involve eradicating entrenched populations on islands, rather than preventing rats getting in. The motives are different too: Alberta’s move was largely economic.

“I think underlying a lot of eradications around the world is a cost-benefit analysis, but it’s very difficult to quantify and in most cases we’re doing it for the conservation of native wildlife rather than through a financial perspective,” says Tony Martin, who led the recent rat eradication project on South Georgia in the South Atlantic.

There, rats were poisoned by bait dropped from helicopters in an eight-year project that cost £10m. Martin’s work was largely funded by donations; he says applying a financial perspective to eradication projects might mean “that money to do the work is more readily available”.

He says that while the two projects were very different, he has “enormous admiration” for what Alberta has achieved. “The fact that they have done so much better than everywhere else in the world is absolutely astonishing. This is unique; it’s not just a town that they’ve managed to keep rat-free, it’s a vast area of terrain.”

He highlights public sentiment as the “single most important factor” in successful projects, saying: “You need to have the interest and the support of the people to carry it out.” Opposition from just a few can derail them – on Australia’s Lord Howe Island, rat eradication has just begun after 20 years of argument. Looming is New Zealand, which has announced an ambitious project to rid itself of introduced predators by 2050 to protect its biodiversity. The idea has been hailed by many, but already there are plenty of critical voices.

In Alberta, there doesn’t seem to be much debate over rat control. McTavish says when she moved there in 2007, she noticed people “seemed very proud” of it. “It seemed to be linked with the identity of Alberta: Being Albertan was knowing this and participating in it,” she says.

Phil Merrill says public support is crucial. “If we have an infestation in someone’s yard, we hear about it right now. We know people are going to report it.” There are a few dissenters – people who oppose the pet rat ban (some flout the law and there’s a three-year-old petition to change it) and parts of the pet industry who raise snakes (rats must be frozen). But mostly “people are very, very happy they don’t have to deal with rats”.

“We get a few animal lovers that think we’re picking on rats and I guess we are, but we have a real good argument: we love native rats – muskrats, packrats. If he can live in the environment without man, great. But if he has to have our food and our garbage and our shelter, then we don’t want him.”

To comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Capital, please head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called "If You Only Read 6 Things This Week". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.