One hundred years ago the United States went dry. A temperance movement had swept the country, culminating with the passage of the 18th Amendment in 1919, which banned the sale of alcohol. The formal legal document, the National Prohibition Act (better known as the Volstead Act) went into effect Jan. 17, 1920. Last week marked the 100th anniversary of the country going sober.

Except it didn’t.

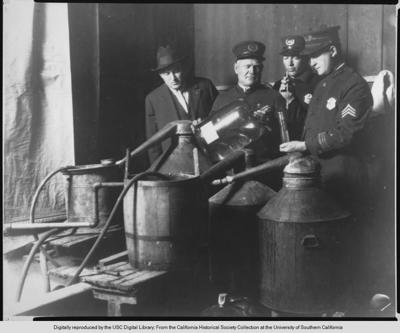

Officially it was illegal, but drinking thrived, thanks to a network of bootleggers, hidden speakeasies, and corrupt officials. In Los Angeles in particular,14 years of prohibition saw criminal networks dominate the city and some of the early infrastructure of L.A. turned into smuggling dens, particularly in Downtown, according to Kelly Wallace, a specialist in California history with the Los Angeles Public Library.

The new law drastically affected Downtown, and quickly. On Jan. 20, 1920, 35,000 gallons of wine were emptied in the sewer at the North Cucamonga Winery at 845 N. Alameda St., according to a Los Angeles Times article from that day. Scenes like that took place across the city, and in the halls of power, the people overseeing the saloons in Downtown reworked their system to deal with the new law.

Prohibition and the Volstead Act did not hit Los Angeles in a vacuum. The wider Los Angeles area had been divided as the temperance movement swept across the country. Some cities, such as Venice and Santa Monica, had gone dry ahead of 1920, while others like Vernon and Watts flourished, according to Richard Schave, a local historian and co-founder of the history-focused Esotouric tour company. A racketeering and bookkeeping network headed by one Charles Crawford was the dominant syndicate at the time, and it oversaw a number of the heavily regulated, legal saloons in Los Angeles. When the Volstead Act went into effect, that same system turned criminal, as players like Crawford turned to bootlegging.

Crawford was a major player in what was known as the “City Hall Gang,” as the bootlegging system in Los Angeles went all the way to the top in Downtown. George Cryer, mayor of the city from 1921-1929, had a series of advisors and staffers deeply tied to illegal bars and racketeering systems.

“Almost all of the city government and police were corrupt,” Wallace noted.

Prior to the Volstead Act, saloons and vice were overseen by the Mayor’s Office, in coordination with the LAPD, according to Schave. The then-head of the LAPD Vice Squad, Guy McAfee, was overseeing saloons and brothels particularly around the Historic Core.

Los Angeles as a whole was a hub for alcohol smuggling, Wallace said, in part due to its geography and network of coves. Liquor would be moved in from Mexico or Canada, and then transported inland, often through Downtown.

Prohibition also devastated Los Angeles’ winemaking industry, which was centered around Downtown in what is now Chinatown and Union Station. Already hurt by blight, drought and development, the Volstead Act effectively killed off Downtown’s vineyards. Only a few in California remained, taking advantage of an exemption that allowed for alcohol production for religious purposes—Wallace noted that one Jewish temple in Los Angeles saw its congregation grow from 180 families to more than 1,000 over the course of Prohibition. The San Antonio Winery in Lincoln Heights just on the other side of the Los Angeles River, stayed in operations, making sacramental wine for churches.

The Underground

Speakeasies, by their very nature, were often haphazard and low-key affairs, designed to be able to relocate quickly if need be. Some spaces operated in semi-secret ways. The King Edward Hotel’s King Eddy Saloon originally opened in 1901, and during prohibition kept operating, just while publicly operating as a music store.

Some other familiar spots had their hidden bars. Loew’s State Theatre (now just known as the State Theatre) had a basement speakeasy where both the alcohol and the customers entered via a chute.

“One interesting specific is that in 1927 there were twice as many speakeasies as there had been bars before prohibition had been enacted,” Wallace said. “[prohibition] increased the number of drinking establishments.”

Although many of the speakeasies were temporary, Schave noted that there was a concentration of them on what was then known as “Poundcake Hill,” near Bunker Hill in what now houses the Civic Center. They moved there after many of the old saloons and bordellos that had been in Old Chinatown and what is now the Arts District were shut down in 1918.

A major part of the bootlegging world was the network of tunnels that ran under Downtown. Contrary to some accounts, most of the underground routes already existed and were simply utilized by criminals and clients, Wallace said.

“The tunnels under the Civic Center already existed, and there were many old tunnels under Olvera Street and Old Chinatown,” Wallace said.

By the 1920s, many of these spaces weren’t being used as much. That included Pacific Electric’s network of tunnels, such as the ones that ran through the Subway Terminal Building at Fourth and Hill that used to serve the old Pacific Electric Railway in Los Angeles. Many smaller ones also were used to link different buildings, including the Hotel Rosslyn, which had a basement bar, Wallace noted. But those underground and hidden spots were more aimed for the wider masses, as opposed to the wealthy or powerful.

“There was some thought though that’s for people who weren’t connected,” Wallace said. “If you were connected you could get your alcohol more in the open.”

The Millennium Biltmore Hotel’s famous Gold Room served as a speakeasy and nightclub during the Prohibition Era as well. A mirrored window in the back of the room actually served as a doorway where liquor could be brought into the space, and famous guests could be shuffled out in case of a raid.

Prohibition officially ended on Dec. 5, 1934 with the ratification of the 21st Amendment (the event is celebrated annually on that day by drinking establishments as Repeal Day). By that point, the infrastructure around the underground networks was failing. Speakeasies had shut down. Schave noted that Crawford was killed in 1931 by rivals.

By the end of the 1930s, a major anti-corruption movement hit Los Angeles, with Mayor Fletcher Bowron trying to root out crooked officers and local Downtown activists like Clifford Clinton (of Clifton’s Cafeteria fame) publishing reports on corruption in the city. The dry times have faded into history but remnants of Los Angeles’ prohibition past can still be seen around Downtown.