Martha Is Dead review: horror that confuses being horrible with being horrifying

There's a time and a face

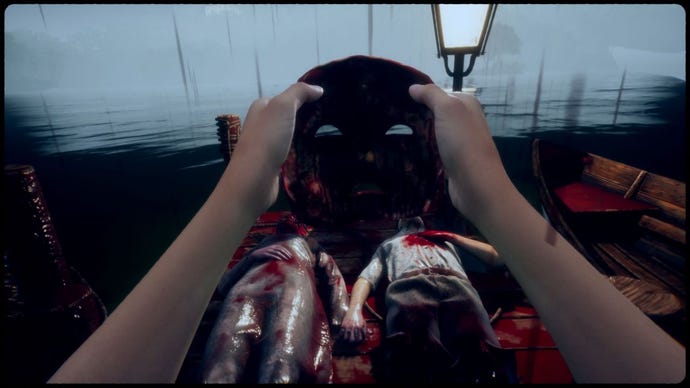

This is the game where you peel a dead woman’s face off. You do it slowly, with a blunt dog tag, making several raggedy incisions before tearing off the face proper. After lingering over the resulting mess of blood, muscle and bulging eyes, you then place your recently drowned identical twin sister’s face over your own. It’s just a dream, but still, this is far from the only time Martha Is Dead insists you do something unspeakable, nor is it even the only time you’re forced to desecrate your sister’s corpse.

Apart from poor writing, these excessive, brute force attempts to disturb define Martha Is Dead. They suck. Horror games are allowed to be horrific, but the way to cultivate real fear is through restraint rather than desensitising bombardment. For the most part Martha just made me frown and go “ew”.

We’re in rural Italy, 1944, towards the end of WW2. You’re Giulia, the daughter of a fascist general, though that’s just backdrop. After a brief flashback where your nanny reads you a gruesome story about a jealous lover who kills a woman who turns into a murder-ghost, Martha Is Dead opens with you venturing down to the lovely lake nestled in the charming woods behind your pleasantly rustic house - where your sister has not so charmingly just drowned. She’s wearing one of your dresses, so when your parents come rushing to the lake shore and find you cradling her bloated corpse, they assume that you are she. Deadpan narration bluntly explains that your mother has always loathed you while adoring your deaf and now-dead sister, Martha, so you go along with it. Cue the face-peeling nightmare.

It keeps going like this. The plot lurches from one macabre catastrophe to the next, alternating between ostensibly real events and nasty dream sequences where the camera gets to really linger over the latest messed-up body. There’s this backwards assumption that the longer we get to stare at corpse gore the more disturbing it will become, rather than the exact opposite. The most uncomfortable part was worrying that someone might walk into my room and ask me to explain myself.

At least they wouldn’t be exposed to the writing. Showing not telling is a particularly heinous sin when it comes to psychological horror, because it’s hard to care what happens to a character that already seems lifeless. Every significant event in Martha Is Dead is accompanied by a long, long monologue where Giulia recounts how she felt sad or shocked or excited. It doesn’t help that those monologues are delivered from the safe certainty of a future we know Giulia winds up in, leeching any remaining sense of urgency. It all adds up to this disconnect between the drama and the player, a non-suspension of disbelief where the artifice overshadows the art. You get an “ew”, not an “argh”.

Every significant event in Martha Is Dead is accompanied by a long, long monologue where Giulia recounts how she felt sad or shocked or excited.

While the plot itself veers about wildly, the pacing can feel ponderous. Early on you’re introduced to your old-timey camera, complete with separate dials for exposure and focus, alongside attachments for taking photos in different lighting and weather conditions. You’re encouraged to mess about with it and take photos whenever you fancy, though there are other, prettier and less clunky games dedicated to that craft. I only brought it out whenever the plot called for it, which it frequently does, often to take a photo of (surprise surprise) a body. This is the 40s, so to actually develop those photos you have to trudge back to your basement’s darkroom and faff through exposing the film and dipping it into those little baths. It’s charming the first time, dull by the third. You only get to see an indistinct negative of each photo before you develop it, too, and they’re not sorted for you, so good luck picking out the plot-critical one if you have gone snap-happy. It tripped me up, even though I’d only taken a couple of accidental extras.

Bafflingly, time-wasting repetition is also baked into parts that are supposed to be actively scary. There are a few dream scenes that have you racing through the woods at night, building sentences out of words that you select by either running left or right. If they were more freeform, those sequences could work as unsettling little tidbits of player expression - but no, pick the wrong one and you get sent back to the beginning. That trial and error structure comes back with a vengeance in a later part of the game, where you have to agonisingly reconstruct a scene using naked, emaciated puppets. Again, the scariest prospect was someone walking in.

Worse still is the side plot where you can choose to dob your dad in and help the anti-fascist resistance. I’d have been all for it if it didn’t mean laboriously deciphering and sending actual morse code via a stashed telegram machine, which involves an additional compounding layer of tedium involved with matching letters to code words. It’s presented as a decision between loyalty to your family or your conscience, but really it’s a choice between spending 20 minutes doing grunt work or moving on with your life.

There are technical faults, too. Some quest markers never appeared, while completed ones stuck around. There’s a bicycle that’s barely worth using thanks to all the invisible boundaries it can’t cross, and the way it judders around in the small area where it’s actually usable. Most of the screenshots in this review are taken with ray-tracing and DLSS, but I had to stop booting into that version of the game because it kept stuttering, no matter which settings I used. Even without them, stuttering persisted, especially whenever I went down a certain staircase. That is not the way you want your horror game to be jarring.

There are small, fleeting glimpses at what could have been. A few scenes dip into strange, surreal imagery that might have been genuinely unsettling if I hadn’t been desensitised from all the corpse ogling. In any case, though, those scenes don’t build towards a satisfying conclusion. Near the end you’re asked a series of questions about which events you think were real, and as best I can tell the game goes along with whichever answers you choose to give. There’s nothing wrong with a dash of ambiguity, but I’d rather not be drenched in it - and it’s a poor companion to indifference.

There are plenty of grievances I haven’t had room to mention, nor to stress the cumulative misery of clunky writing combined with cheap attempts to go beyond the pale. Even if it weren’t so needlessly and extensively graphic, there’s a fixation on things that can go wrong with a woman’s body that would still leave a sour taste. The story as a whole is a series of rug pulls, but ones which left me standing nonplussed while the rug puller lurched haphazardly from foot to foot. A parade of ghost sharks, clumsily jumped. I suspect Martha Is Dead will be remembered as the game where you peel a dead woman’s face off, but it’s better off forgotten.