The Loaded Language Shaping the Trans Conversation

To focus on “desisters”—people who experience gender dysphoria and then ultimately decide not to transition—is to focus on the rarest of cases, and to ignore the vastly more common experience of trans teens: that of being second-guessed.

It’s a scene I know well: the awkward first moments when I’ve just stepped into a stranger’s house. Looking around, taking in the family portraits, the furniture, the smells, placating the family dog. The handshakes and offers of coffee or water. The first, tentative moment of introduction to the young person who knows she’s about to be asked all kinds of personal questions about her identity and desires. Who knows that, at some point, she will leave the room and her parents will tell a stranger all about her childhood, her gender development, how they feel about how she looks, what she likes to play with or do, who she is. In my fantasy, the journalist Jesse Singal felt similarly tentative when he met Claire, one of the pre-teens who appears in his recent Atlantic cover story, “When Children Say They’re Trans.” Claire, a gender-nonconforming child, for a time considers transitioning before deciding against it. (Claire is a pseudonym used in the article.) She is young, still living at home. Her life stretches before her, and we, the readers, are left to make sense of what she’s said.

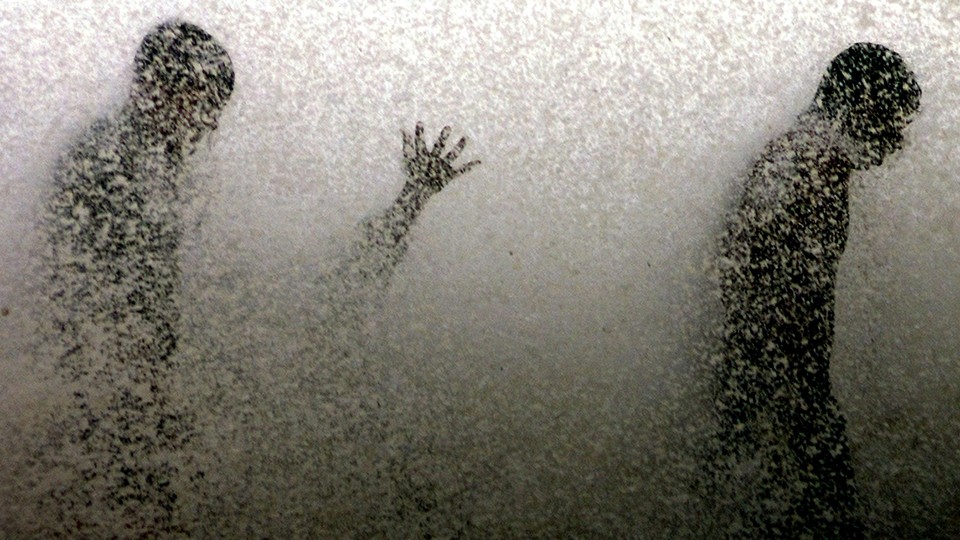

I am a sociologist, and I have spent the last nine years studying trans and gender-nonconforming young people and their families, using interview methodologies not dissimilar from Singal’s. While it is true that there are “no easy answers” to the questions raised by significantly gender-nonconforming kids, believing that the most important issue is whether Claire is “really” trans misses the point of the complexity of gender transitions. Claire’s story hasn’t ended; she is still very much a young person and a work in progress. And it isn’t up to Claire’s parents, or Jesse Singal, or the general public to determine where she will end up in time. That is a question for Claire to answer herself, ideally with the love and support of parents and professionals who can be fully present and supportive, no matter how circuitous her journey may be. This is a distinction of great political importance. To position Claire as a “desister” in the way Singal did is to participate in an inherently stigmatizing discourse with a very particular and damaging social history. The frames journalists use to discuss these controversial issues are themselves political and moral decisions, and ones of great consequence. They set the terms by which the public understands trans youth.

This is an intense cultural moment in America around what Singal calls “gender-identity awareness.” Whereas in decades past, parents would send gender-nonconforming children to psychologists to be “cured” of their deviance, now some (though certainly not all) families are doing a range of other things. They are allowing children greater latitude to violate gender norms, to assert identities that differ from those assigned at birth, and in some cases, they are allowing children to transition from one gender category to another. All of this cultural change has left many adults (journalists, psychologists, politicians, educators, and, of course, parents themselves) feeling anxious and uncertain.

How should adults respond to identity claims by children? How ought parents to interpret the things very young children—those who can’t yet make ardent identity claims—say and do? In this uncertain context, it is tempting to make examples out of individual children. But the children whom journalists and academics like myself choose to highlight, and the ways we tell their stories, matter. By opening his article with Claire, and situating the complexities of parents’ experiences around the notion that a child’s gender nonconformity can simply resolve and is then over and settled, Singal is reading an ending on to a story that is far from over. Claire is 16 and still living with her parents. We have no idea where she will end up in time. And the relief Singal depicts at the resolution of her gender transgression belies both his and Claire’s parents’ investment in a cisgender future for Claire, not necessarily an authentic gender future.

It’s worth interrogating the origins and development of the idea of “desistence.” This is not a value-neutral term. As the trans writer Julia Serano has noted, citing academic research, in criminological contexts, “desistence” is used to denote the cessation of offensive or antisocial behavior. The term was adopted by conservative clinicians as a descriptor for gender-nonconforming children who grow into cisgender adulthoods (whether they were coerced into doing so through corrective therapies or simply changed their minds). It comes from an outmoded psychology organized around the assumption that there are only two forms of gender: normal and disordered. A person was once pathological or disordered, but now they are back on “normal” ground. The idea that some children desist functions to support efforts to socialize children out of gender deviance, and to interpret those who do desist or re-transition as victims of abuse or false consciousness. (They were “pushed too quickly into transition” or “too young to really understand who or what they were.”)

But now, there are increasing numbers of clinicians who reject all of these premises, who don’t think that trans identities are any less desirable than cisgender identities. And transitions can look many different ways. Many staunchly affirmative clinicians, like the psychologist Diane Ehrensaft, whom Singal includes in his piece, believe that there is a “constellation of a gendered self,” one that, rather than always moving in a linear transition from point to point, weaves, like all development does, through many stages of delight, joy, loss, and ambivalence.

This does not, however, mean that children aren’t transgender. It means that the adults in their lives must approach those children with care, patience, and an openness to allowing them to fully and uncritically explore all gender trajectories without fear of adult disappointment or retribution. And many do. As I explain in my book, clinicians work in relationship with children and families to explore the many different gender trajectories open to any particular child, before settling on social and/or medical transition. As new clinical guidelines are introduced, they incorporate discussions of the differences between expression and identity, and between exploration and transition.

It’s not surprising that as ever-greater numbers of children publicly express gender-nonconforming and trans identities, there will be stories of some who live as trans and then re-transition back to cisgender identities. Making the assumption that these are stories of overeager pro-trans clinicians and parents is misguided. Some trans people re-transition because of pressure or abuse from family and others close to them, and some because social stigma makes living in the world too difficult. Some re-transition because the gender they try simply doesn’t fit. Some of these people say they don’t regret their time in transition, and say they absolutely needed the experience of transition to develop a self they could rest in. Some de-transitioned trans people explicitly ask that their stories not be used to complicate access to transition. Whatever the reasons, a critical point is that these are rare cases: In my own conversations, even the most conservative clinicians told me they rarely, if ever, see someone make a full social and medical transition and then experience serious regret.

This is a precarious moment for trans rights. Two Ohio lawmakers recently proposed legislation that allows parents to withhold gender-affirming care from explicitly trans-identified minors and, unbelievably enough, makes it a fourth-degree felony for school employees or volunteers to fail to report a child’s gender-transgressive behavior in school to parents. This seems a far cry from Jesse Singal’s apparent perception of the world, in which a cohort of adolescents, with support from their overeager parents, may be hastily adopting trans identities. Indeed, in my research, I found the issue was much more often how to access clinically competent, trans-affirming care for children who desperately needed it, even in the largest American cities.

The sociologist Ken Plummer, an emeritus professor at the University of Essex, once wrote that “stories are social actions, embedded in social worlds.” It might be tempting to look to so-called “desisters” to frame the complexity of childhood gender transitions for the adults who surround them. But this is a dangerous way in, designed to allay the anxieties of adults who withhold affirmation and care from gender-nonconforming youth, to reinforce the out-of-date idea that cisgender lives are the ones most worth living, and to stack the political deck so that it feels less risky to withhold gender recognition from trans children than to offer them room to decide the contours of their lives and identities for themselves.