Baiting the Booboisie

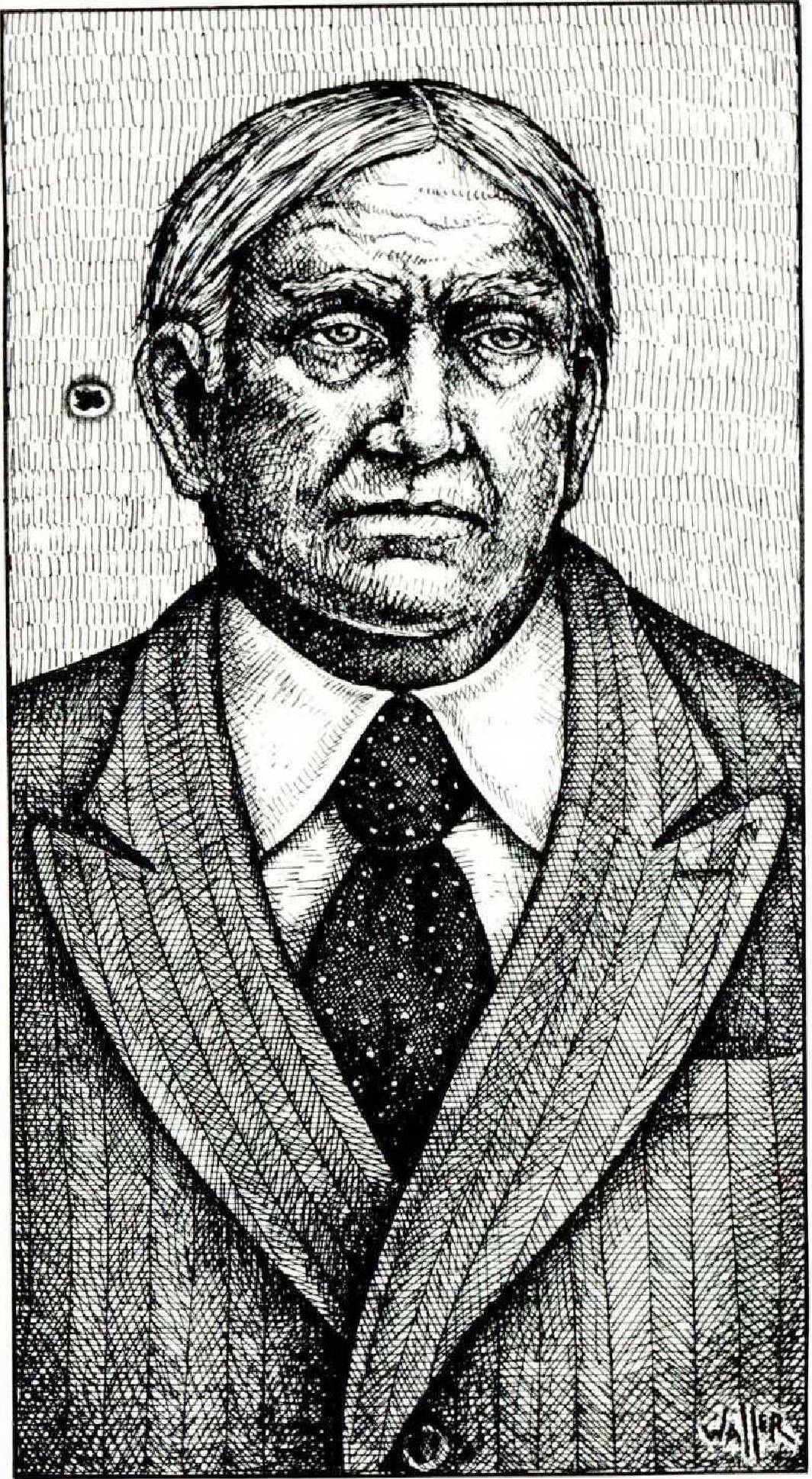

Who was H. L. Mencken? When his name is mentioned nowadays, the figure that comes to mind, at least to middle-aged people like myself, is that of a crusty buck in a crumpled seersucker suit chomping a cigar as he sits at a typewriter (the kind described as “battered”) and covers—for the sixth time, the tenth?—a Republican or Democratic national convention in Philadelphia.

Specialists in American letters don’t stop here, of course; they connect Mencken with the literary campaign, fought early in this century, for “honest realism” in fiction (Dreiser, Sherwood Anderson, Sinclair Lewis); or with the development of interest, among professional linguists, in the American vernacular (Mencken led the way with a tome called The American Language); or with the creation, in the twenties, of one of the most influential magazines of the period (Mencken and George Jean Nathan founded The American Mercury). Baltimoreans fill out the picture with other colors, remembering Mencken as a vocal enthusiast of the town (his birthplace and lifelong residence), connoisseur of its beers, passionate participant in its musical culture. But for outsiders the image that returns is, as I say, plainer—old-timey, down-to-earth, vaguely folk-heroic: Mencken the straight-talking, no-nonsense debunker, the Working Newspaperman.

For Charles Fecher, author of MENCKEN: A Study of His Thought (Knopf, $15.00), neither that image nor those shaped by conventional literary historians is appropriate. His Study, by turns a biography and an appreciation, offers chapters on Mencken’s family background and literary style, together with a chronology of the life and a bibliographical note. But the center consists of four extended sections treating “The Philosopher,” “The Political Theorist,” “The Critic,” and “The Philologian.” And the assumption throughout, as the title indicates, is that Mencken matters most as a thinker. He ranks in some respects, says Fecher, “above and beyond . . . Goethe, Sainte-Beuve, and Coleridge,” since his criticism “literally changed the whole course of literature in the United States.” As the author of The American Language, he functioned as a linguistic Moses who “freed the living tongue of more than a hundred million people from bondage to archaic rules and pointed it in the direction of a power, growth, and vigor that it had not known since Elizabethan times.” And as guardian of the national conscience, he elevated the quality of American political life:

... if there is not quite as much corruption as there used to be, if today’s public and governmental figures are a cut above the Bryans and Hardings and Coolidges of a past generation, if the American people do not take “beaters of breasts” quite as seriously as their fathers did, he must deserve a large share of the credit for these facts . . .

These are, I’m afraid, extravagant claims, but it doesn’t follow that Fecher’s angle of approach—the notion of treating Mencken as a thinker—would have struck the subject himself as outlandish. The author of Newspaper Days appears to have held his work in far higher esteem than he could have held that of any mere Working Newspaperman, folk-hero or no. Indeed, his confidence in his power as a knower—a mastermind—was little short of monumental.

He was certain, to begin with, that he knew the difference between true greatness and paste. (Jesus Christ was someone of “stupendous ignorance,” “probably dirty in person”; Dante was “a wop boob”; Thomas Henry Huxley was “perhaps the greatest Englishman of all time.”) He knew, furthermore, that history was an easy subject, bare of mystery and cunning passages. The past is best seen as a period of protracted waiting—for Francis Bacon and the challenge to religion. The present equals Progress & Science.

(“The Seventeenth Century, and especially the latter half thereof, saw greater progress than had been made in the twenty centuries preceding—almost as much, indeed, as was destined to be made in the Nineteenth and Twentieth.”) The future is total freedom, banishment of faith, ascent to the understanding that Christianity “deserves no more respect than a pile of garbage.”

As for Politics, it too was perfectly clear, sound knowledge in this field amounting only to awareness that democracy—“the art and science of running the circus from the monkeycage”—is a disaster, “the worst evil of the present-day world.” Ethics was equally easy. The bottom line, as regards right relations among men, is that human creatures divide neatly into two camps: superior beings here (“the intelligent, minority”), a mass of creeps there (“the booboisie,” “Homo boobiensis,” “deadheads,” “lower orders,” “ignoramuses,” “poltroons,” “the vast herd of human blanks”).

It’s possible, of course, to overcomplicate these and other clear ideas—by introducing a clump of detail. The vast herd, as Mencken saw it, isn’t wholly undifferentiated. One group, often referred to by him as “coons” or “niggeros,” has never had a prayer of selfimprovement except when aided by admixtures of white man’s blood. (“. . . it is commonplace that nearly all Negroes who rise above the general are of mixed blood, usually with the white predominating. . . .”) And the herd includes city blanks as well as country blanks, two quite different categories. (“Even the lowest varieties of city workmen are at least superior to peasants.”) And while the idea that a huge gap separates superiors from inferiors is universally valid, it’s a fact that some nationstates, especially America, are thinner than others in top people. The United States is a “buffoon among the great nations.” Its citizens have no notion of what constitutes human dignity (the “concept of honor ... is incomprehensible to most Americans”), and they rank as

. . . the most timorous, sniveling, poltroonish, ignominious mob of serfs and goosesteppers ever gathered under one flag in Christendom since the end of the Middle Ages

But a clutter of subsets and qualifications is, to repeat, unnecessary. All knowledge flows from the central principle, that of the nonexistence, among humankind, of a common bond. Grasp this principle and —in Mencken’s view—most intellectual and moral problems are solved.

As a writer, Charles Fecher, obviously a Mencken idolator, is grammatically shaky (“their critical writings . . . is”), and as a student of thought, he doesn’t often cut deep. There’s an evident discontinuity between Mencken’s scorn of America as “essentially a commonwealth of third-rate men” and his delight—it breathes everywhere in The American Language— in the spring and bite of common American speech. And there’s a comparable discontinuity between his sneers at the “inert mob” and his admirable praise of Dreiser’s broadly humane response, in Sister Carrie and An American Tragedy, to feelings and fantasies of the humble. By addressing such discontinuities, Mencken’s admirers place themselves in position to penetrate their idol rather than merely to puff him. By ignoring them, they direct attention away from precisely the dimension that makes the man undismissible even by those who find him generally repugnant. Charles Fecher ignores the discontinuities.

But if this book fails as an effort to refashion Mencken’s image, it’s surprisingly effective—inadvertently—as a moral treatise. It amounts, in fact, to a vivid dramatization of a major weakness of wits, namely self-importance, the habit of denying the seriousness of serious things on the theory that personal brightness is all. H. L. Mencken was the kind of person who can’t shut down the trivializing joke-machine even when its products are monstrous irrelevancies. Discussing the sufferings of Hiroshima victims, he begins with the torments of women and children “slowly fried or roasted to death like people burned by radium or X-rays”— and at once races on into inexplicable clergy-baiting: “In many cases their agonies were prolonged, and they suffered worse than any bishop will ever suffer in hell.” This same incapacity to sustain humanly commensurate response turns up in Charles Fecher; his measure of the most appalling atrocity, for example, is the effect it has upon Mencken or Mencken’s friends. (Fecher complains at the “lighthearted way in which [Mencken] brushed off Nazi treatment of the Jews” on the single ground that the lightheartedness “hurt Alfred Knopf. . . .”) The impression left is that self-importance on this scale locks a soul into not only the smallest but the most airless of small worlds.

Deciding where, on the contemporary scene, Mencken’s inheritors—haters of The Others—are located isn’t easy. Monumental egocentricity, conviction of the vastness of one’s intellectual range, and longing to crush the boobs are conjoined in Norman Mailer, but Mailer’s self-awareness is shrewder and richer than Mencken’s. Probably the true inheritors of this mantle are to be found in the new race of egoand self-developers, fans of pop psychological manuals that teach people how to despise everybody except Number One. Once upon a time, before the various floods— before the booboisie was fully instructed in the hatefulness of Gopher Prairie and Oak Park—a Baltimore sage could plump himself up into the aristocracy by calling his neighbors cowards and poltroons. But time passes and democracy democratizes . . . On every street corner people stand reading Sinclair Lewis and H. L. Mencken—until at length the unthinkable occurs: the stinking herd decides it wants a piece of the action, its own right to dismiss. Whereupon Robert Ringer and the gospel of Enlightened Selfishness. Boobbaiting and Number One mongering are related enterprises, in a word, efforts by “superiors” and “inferiors” continually (and in assumed isolation from each other) to invent new languages in which to justify refusals of communication with Outsiders. And, for that reason, H. L. Mencken remains, to this day, one of us.

At the 1934 Gridiron Club dinner in Washington—omit the occasion from any survey, short or long, of the Mencken story, and an important meaning is lost—the hero of The Smart Set endured a fearful putdown. That is to say, his standard gestures of contempt were brought fully, if briefly, into social light for examination by a master parodist— someone who happened also to be doing more, at the time, than most of his fellows to strengthen solidarity as a value. Speaking first at the dinner, Mencken saluted the audience (mainly reporters and editors, with a scattering of politicians) as “fellow subjects of the Reich,” and went on to assert that for two years the Bill of Rights had been inoperative and that the New Deal would take the whole country to ruin before long. A little later, as Charles Feeher describes the event,

. . . it was [FDR’s] turn to speak. Flashing his famous smile, he acknowledged “my old friend, Henry Mencken.” He made a few humorous introductory remarks. But after that all pleasantry vanished: within a few minutes he was launched upon a diatribe against journalism and newspapermen so all-embracing and vicious that cold chills began to run up and down the spines of his listeners. “The majority of [reporters],” Roosevelt declared, “in almost every American city, are still ignoramuses, and proud of it. All the knowledge that they pack into their brains is, in every reasonable cultural sense, useless; it is the sort of knowledge that belongs, not to a professional man, but to a police captain, a railway mail-clerk, or a board-boy in a brokerage house. . . . There are managing editors in the United States, and scores of them, who have never heard of Kant or Johannes Müller and never read the Constitution of the United States; there are city editors who do not know what a symphony is, or a streptococcus, or the Statute of Frauds; there are reporters by the thousand who could not pass the entrance examinations for Harvard or Tuskegee, or even Yale.”

Gradually it began to dawn upon his audience that the President was not really making a speech at all; he was simply quoting an extremely long excerpt from “Journalism in America,” which had appeared as an editorial in the October 1924 issue of The American Mercury and subsequently been included in [Mencken’s sixth volume of] Prejudices. . . . Every eye in the room focused upon Mencken, who . . . turned the color of “oxblood porcelain.” . . . As Roosevelt was wheeled out of the hall he paused at Mencken’s table for a genial handshake.

Mr. Feeher believes that this was a disgraceful thing for a Chief Executive to do—“by any standard at all, unfair”— and, while I’m uncertain about that, I’d agree that it’s mean to be pleased at another’s humiliation. I’d also grant that the passage Roosevelt quoted is first-class Mencken, and that the press deserved the vilification. And I’m aware that FDR’s motives weren’t exalted. Might not the Chief Executive have meant to demonstrate, by savaging Mencken in this way, that contempt and cowardice (telling off journalists behind their backs and then breaking bread with them as a friend) are two sides of the same coin? Might he not have intended a pertinent moral comment on the nature of traffickers in mockery? Not a chance. This President, like some others before and after him, was socking it to an enemy with a shrug. Despite everything, though, a hint of rough justice hangs round the occasion: I’d love to have been there.