Why Breitbart Started Hating The Left

The conservative culture warrior shares stories from his privileged childhood, debauched college days, and formative political years

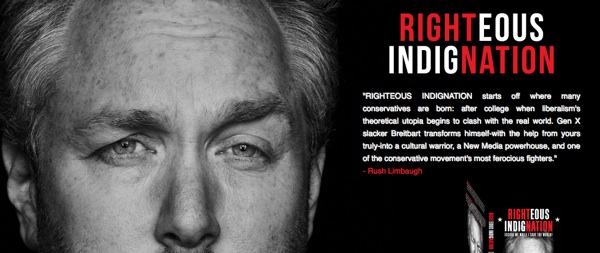

What did Andrew Breitbart do before he became a Web publisher and culture warrior? In the second chapter of his book, Righteous Indignation, we're given the early part of his biography, including his high school years in a wealthy Los Angeles neighborhood, college at Tulane University, and his subsequent return to Southern California.

His father ran a successful restaurant. His mother worked in a bank. They were Republicans, but seldom talked about it. "Their attitude towards the people around them living the Hollywood liberal lifestyle were grounded in a reality and a normalcy and a decency," he writes. They didn't care about celebrity, or that their comfortably upper-middle-class lifestyle still left them with less money than their neighbors. "While many of my friends' parents were gallivanting off to Europe and leaving their kids at home - for some reason, my parents considered this a form of child abuse - my parents opted to buy a thirty-three foot motor home, the Executive, and took my sister and me on a formative cross-country trip," Breitbart remembers. "...While my parents' house had a pool and four bedrooms and a scenic canyon view of West Los Angeles, it couldn't compete with the beachfront Malibu property that two of my friends at school occupied."

In some ways, this childhood sounds a lot like my own. My parents are decent, hardworking people who tend to vote Republican. Raised in an upper-middle-class neighborhood - far less ritzy than Brentwood, but no less safe or comfortable - I always had everything that I needed. Still, the single-story, three bedroom house where I grew up couldn't compete with the pricey estates and beach houses where some of my classmates lived. Like Andrew Breitbart, I sometimes look back on my youth as if I'm Nick Carraway, marveling at the seductive but ultimately bankrupt subculture of extreme wealth that I occasionally observed up close. There are plenty of perfectly wonderful rich families, of course. But at my high school, the extreme troublemakers always seemed to come from the richest families, where they were raised by hired help.

There is one seemingly small difference in our experiences. In Orange County, where I grew up, it wasn't just my parents who were more or less political conservatives - so were the subset of very rich families who seemed to live their lives according to a completely different value system. But Andrew Breitbart is from a community where the very rich folks with seductive lifestyles and blinkered values were mostly liberals. When I look back on childhood, and my worst behaved, most morally suspect classmates, I see quite clearly that it was neither partisan nor ideological affiliation that shaped their pathologies. Reflecting on his upbringing, Andrew Breitbart sees the decent conservatism of his parents, the inferior values of rich families who were liberal, and attributes the difference to their politics. This misunderstands the relationship between moral failings and ideology. And simply watching The Real Housewives Of Orange County and then The Real Housewives of New York City is enough to grasp what I learned by experience.

Breitbart isn't good at understanding ideology even on its own. Take the anecdote about his onetime friend Mike, a guy he meets while working as a pizza deliver boy in high school. They bonded over British alt-rock. Then Mike began turning Breitbart onto "the highbrow literary and philosophical tracts of obscure philosophers," and other liberal publications like The Utne Reader and LA Weekly.

Here's a telling passage:

Mike gave me a CliffsNotes version of the leftist point of view, a romanticized, James Dean-ish, moral-relativist, everything-is-pointless crash course on how thinking people should, in fact, think. I imbibed it without question. So when it came time for college, it was as if the professors in my freshman classes were speaking the exact same language I was. Through some form of osmosis, I considered myself a liberal. As a result, there would be no culture shock when I entered Tulane.

Assertions like this one ought to embarrass conservative authors. Do guys like Mike exist? Yes. That Breitbart cites his attitudes as a Cliffs Notes version of "the" leftist point of view - it's monolithic, you see - betrays ignorance of the very thing he has dedicated his career to attacking.

Has he never encountered an earnest twenty-something canvassing for Green Peace? Or a student activist demanding that the dining hall workers be given better health insurance? Did he miss the giant immigration rights marches in Brentwood? Is he unaware of Amnesty International? Or the establishment progressive wonks eagerly trying to figure out how to bend the Medicare cost curve? There are a lot of critiques one could marshal against these folks, who embody various leftist stereotypes. The notion that they're all "everything-is-pointless" moral relativists can be taken seriously only if you get all of your news from Breitbart sponsored Web sites.

In college, Breitbart himself was the rebel without a cause. He chose a school in New Orleans because "I wanted to rock out with my cock out," he writes. Once there, he joined a frat, did cocaine, drank and drove, and developed a gambling problem: "With the passing of every drunken and debauched week, I could feel the acute sense of right and wrong that had been bestowed upon me by my parents fading further away," he writes. "I started to see things in shades of gray. And the courses that I was supposedly taking, mostly in the Humanities department, seemed to jibe perfectly with this new outlook."

Again, the astute reader must call bullshit.

What specifically about his humanities classes seemed to jibe with the frat boy lifestyle? I had a different reading of John Rawls, Toni Morrison, and Michel Foucault. Eventually, he declared a major in American Studies, writing that "it ensured I would accomplish nothing in the next few years."

Tom Wolfe seemed to do okay with his degree.

After graduation, Breitbart returned to LA, and entry level jobs as a waiter and a Hollywood delivery boy. It is in this period that the seeds of his hatred for the entertainment industry, the Democratic Part and the news media were planted. Hanging around the big studios, he astutely grasped that he should avoid a career in that amoral subculture at all costs. Around the same time, Clarence Thomas was nominated to the Supreme Court. Breitbart felt outraged by the Democratic Senators opposing him. To this day, he insists that they lacked solid evidence - and that the national media didn't call them out. "I did not leave the Clarence Thomas hearings a Republican," he writes, but "this was the exact point I realized not just that I disagreed with the Democratic Party but, more important, that the media were its dominant partner in crime."

That brings us to the least self-aware passage of the book thus far:

It was impossible for me to not recognize that Clarence Thomas being black was part of the story. How in hell could white Americans Leahy, Biden, and Metzenbaum, let alone former KKK grand pooh-bah Robert Byrd and Chappaquiddick's very own Ted Kenned, so arrogantly excoriate this man whose personal narrative from sharecropper's grandson to Supreme Court nominee embodied the American dream? A narrative that would send a clear signal to African-Americans that anything is possible in this country?

Yes, "white American" Andrew Breitbart would never dream of excoriating a black person with a personal narrative that embodies the American dream and sends a signal to African-Americans that anything is possible!

So we return to the theme of Breitbart professing to hate some perversion of decency or moral values, and then engaging in that very same behavior. He criticizes the left for its "nihilism" and "moral relativism." Simultaneously, he asserts that he is fueled on a day to day basis by the hatred of his critics, and dedicates himself not to building something, or advancing a positive agenda, but to destroying the institutional left. Told a tactic he adopts is objectively unethical, does he insists that it is, in fact, objectively moral? Nope. He retorts that what he does is justified by behavior on the left that is at least as bad and probably even worse. What explains these contradictions?

Perhaps we'll find out in a future chapter.