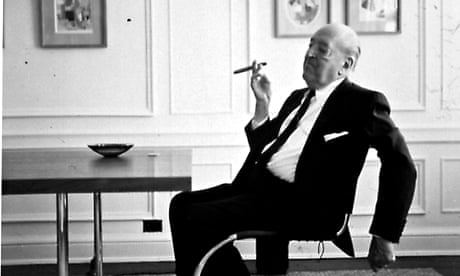

"Less is more"; "God is in the detail"; "I don't want to be interesting, I want to be good" – Ludwig Mies van der Rohe is a figure who, even among those who would be pressed to name his works, exerts influence through his aphorisms. That he might also be credited with inventing the glass skyscraper adds much more to his importance. Among architects of the modern movement, he was Mies, part of a binary godhead with Le Corbusier, or Corb – names for whom four letters were enough. Their monosyllables also had the quality of "stone" or "steel", of something fundamental to construction.

Mies was easy to caricature, and was by his opponents, especially when, from the 1960s onwards, he became identified with American corporate power. He was a Teutonic control freak. He was inhumane. His buildings were all the same; when Castro's revolution scuppered his administration building for Bacardi in Cuba, he seemingly repurposed the design as the New National Gallery in Berlin. His works were nothing but glass boxes. They were embarrassed by such signs of human life as blinds, whose random arrangements disturbed the implacable steel grids of his elevations. To which his response was to design them with only three settings – open, closed, and half-open.

It didn't help that he was a bit of a bastard – for example in his personal and professional dealings with women – and notoriously tried to get along with the Nazis, including signing a petition in support of Hitler (though he had also designed a monument to the left-wing Spartacist uprising). But then, with alarming rapidity, the sub-hippy postmodernists who challenged Mies themselves became identified with American corporate power. Ever since the 1980s, a long, slow reappraisal of Mies has been going on, of which Detlef Mertins's imposing 500-page work sets out to be the definitive statement.

Mertins emphasises his sensuality, his "ethereal" and "luminous" qualities, and argues that, beyond the apparent certainty and single-mindedness of his buildings, there is complexity and doubt. Above all, Mertins stresses Mies's readings of philosophy. Mies was not a great writer of theory himself, and always stressed the importance of actually building things, but he saw building as a way of enacting spiritual ideas.

His philosophy included pessimism – "Is the world as it presents itself bearable for a man?" he asked. According to Mertins, Mies would have learned from Nietzsche that "under the conditions of modern homelessness and nihilism, life could and should be lived as an experiment and adventure of the soul". The intent of his buildings is not to oppress but "to help nurture the art of self-fashioning in others". By denying easy consolations and placebos, they are supposed to challenge you, so that you can lead your life on a higher plane. Which, if it happens, is a form of liberation.

Thus his glass houses were not supposed to be cosy or domestic, but to put you into a more intense relationship with their natural surroundings. He acknowledged that it would be difficult to show art in his Berlin gallery, but argued that it would be a great possibility to find new ways of doing so, provoked by his architecture. Mertins points out how many extraordinary and varied exhibitions have in fact been presented there.

One question is, liberation for whom? Not Edith Farnsworth, who was made angry and miserable by the nonetheless extraordinary house that Mies designed for her, and not the African-American residents of the Mecca building in Chicago, demolished to make way for Mies's Illinois Institute of Technology. The architect was not directly responsible for their eviction, but the suspicion remains that Mies's spirituality could be a sort of ultra-luxury, best suited to people such as the extremely rich Tugendhats who, in the few years before they were forced out by the Nazis, loved the expensive and beautiful house that Mies made for them in Brno, Czechoslovakia. All of which makes one of the more interesting projects in the book, Lafayette Park in Detroit, a middle-income housing project that, according to Mertins, still works well.

As for you, dear reader, you will yourself be challenged, both by the book's £100 price and by Mertins's intellectually demanding text. Like its subject, it demands to be taken seriously. But if you're up for it, it's worth it.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion