“Cities in flames seen from above are one of the toughest semesters for an architectural student.” This was Frei Otto, the influential German architect, engineer, teacher and writer, who has died at the age of 89, recollecting his experience as a trainee Luftwaffe fighter pilot. The view from a Messerschmitt Bf 109 as the Third Reich went up in flames, he said, encouraged him to imagine a postwar architecture that would be transparent, democratic, non-hierarchical and free.

He had only just entered architecture school at the Technische Universität, Berlin, when he was called up for military service in the second world war. As he had designed and flown gliders, the Luftwaffe was a natural choice.

However, Otto, whose parents were members of the Deutscher Werkbund, an association of forward-looking artists, designers, architects and patrons founded in 1907, looked down with horror on what the Nazis had created, artistically as well as politically. Their monumental neoclassical buildings standing to attention around parade-ground public squares represented the crushing weight of the Third Reich.

Otto returned to architecture school in Berlin in 1948, before studying for six months at the University of Virginia. In the US, he met his architectural heroes, Charles Eames, Richard Neutra, Eero Saarinen, Frank Lloyd Wright and, above all, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. A former architectural director of the Deutscher Werkbund and the last director of the Bauhaus before the design school was forced to close in 1933, Mies had gone on to teach and shape his radical new architecture in America. His famous dictum “less is more” is one Otto believed in to the core of his being. The duty of the architect was to make as little impact as possible on nature and to learn from natural design – in Otto’s case, from the structures of crab shells, birds’ skulls, spiders’ webs and bubbles on the surface of water.

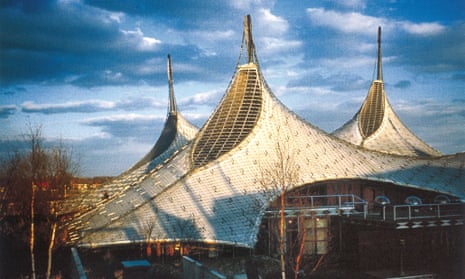

In a long career, starting in 1952 when he set up his own studio in Berlin, Otto worked with fellow architects, engineers, scientists and artists in a spirit of democratic collaboration to create such structural wonders as the floating, net-like roofs of the German pavilion at the innovative Expo 67 in Montreal, the celebrated Summer Olympics stadium in Munich (1972), and the ultra-lightweight aviary at Munich Zoo (1980).

In Britain, a generation of “hi-tech” architects – among them Richard Rogers, Norman Foster, Michael Hopkins and Nicholas Grimshaw – were under Otto’s spell. The lightweight fabric roof of the Mound Stand at Lord’s cricket ground (1987), the bubble-like domes of the Eden Project, Cornwall (2000), and the “bubble-wrap” structure of the National Space Centre, Leicester (2001), are spirited evidence of Otto’s influence.

Born in Siegmar, Saxony, Otto was to have followed in his father’s steps as a sculptor but instead turned to architecture. After his capture in Nuremburg in April 1945, he spent two years in a French PoW camp near Chartres, where he used his burgeoning skill to shape makeshift shelters and other useful structures from minimal means. His postwar studies exposed him to the work of the brilliant Russian structural engineer and polymath Vladimir Shukhov (1853-1939), pioneer of lightweight tensile, gridshell, diagrid and hyperbolic structures more than half a century before computers arrived to help with the calculations involved in such radical designs. In the United States, he was transfixed by the lightweight beauty of the multi-purpose JS Dorton Arena (1952) in Raleigh, North Carolina, designed by the Siberian-born Polish engineer Matthew Nowicki.

Combining teaching in Germany and the US with design work, Otto established a succession of overlapping university research institutes to further the understanding and practice of lightweight structures. These included the Biology and Building group, Berlin, founded with the biologist Johann Gerhard Helmcke, and the Institute of Lightweight Structures, Stuttgart. He was a prolific writer, whose Tensile Structures (two volumes, 1962-66), Biology and Building (1972), Pneu and Bone (1995) and Finding Form: Towards an Architecture of the Minimal (1995) remain engaging and practical.

Married in 1952 to Ingrid Smolla, Otto had five children, one of whom, Christine Otto Kanstinger, qualified as an architect and joined her father in his atelier at Warmbronn near Stuttgart in 1983. Meanwhile, after one of his star German students, Mahmoud Bodo Rasch, became a Muslim in 1974, work flourished in the Middle East, with Otto consulting Rasch on such engaging designs as the “umbrellas” that, from 1992, have opened up in the paved area used for prayer outside the Prophet’s Mosque, Medina, to create shade when the sun is at its fiercest.

The British engineering consultancy Buro Happold also worked on this project, as it did, with Otto and the architects ABK, on a delightful workshop for the Parnham Trust School for Woodland Industries, at Hooke, Dorset. Built in 1989, the workshop’s sinuous vaulted structure was fabricated from stressed and exposed spruce thinnings, a case of nature working hand-in-branch with advanced structural design. A decade later, Otto advised on the design of a pavilion with Buro Happold and the Japanese architect Shigeru Ban for Expo 2000 in Hanover; its roof structure was made entirely of paper.

As with his American friend Buckminster Fuller, Otto’s invention was always in full flow. With his lean, angular frame and shock of white hair, in later life he looked every inch the idealised and strict German scientist-professor. He was, though, a warm humanist, a man who loved nature, and was an idealist. He was always thinking ahead, building, he said, “castles in the sky”, even as he worked to shape environmentally responsible lightweight structures on the ground. Days before he died he was told that he had been awarded the 2015 Pritzker prize for architecture. “Frei stands for freedom,” said Lord Palumbo, chair of the prize jury, “as free and as liberating as a bird … and as compelling in its economy of line and in the improbability of its engineering as it is possible to imagine.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion