My first encounter with Laurent Ponsot was a memorable one, though I had no idea at the time how significant it would become. I was attending an auction at Cru, a downtown New York restaurant that was a mecca for wine buffs before the financial meltdown of 2008, intimations of which were in the air that April night. Bear Stearns had recently collapsed, though you wouldn't have known it from the merriment on display— which included a well-known collector in a pink Kiton jacket slicing the top off a jeroboam of 1945 Pol Roger with a saber.

A few minutes earlier Ponsot, a slender figure with salt-and-pepper hair tied in a ponytail, had taken a seat in back. Amid the revelry he seemed like Banquo's ghost, a messenger from another world. The fourth-generation scion of one of Burgundy's most admired domains, Ponsot was a figure I'd heard of but not met. (The 1985 Domaine Ponsot Clos de la Roche, a wine he'd made with his father, had converted me forever to the wines of France's Côtes d'Or.) At the Cru auction, a large parcel of bottles purported to be old Domaine Ponsot vintages were on offer; Ponsot, knowing they were counterfeits, had flown in to prevent their sale.

Soon enough the auctioneer announced that the lots had been withdrawn. After the groans and boos died down, Ponsot exited, his mission accomplished, at least for the moment. The longer-term project, which he pursued for years, was to find out who was counterfeiting his wines.

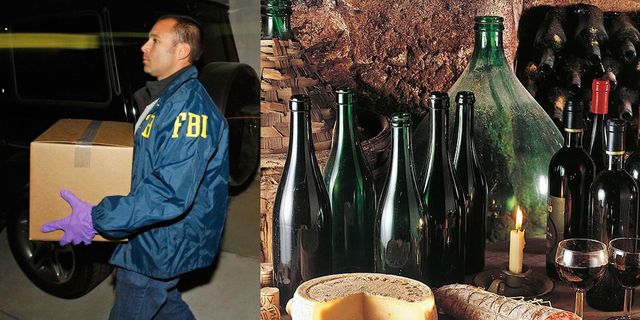

The vendor of the bogus bottles was a 36-year-old Indonesian named Rudy Kurniawan, who would eventually be sent to prison for fraud, thanks to Ponsot and the billionaire investor Bill Koch. A few months after Kurniawan's conviction, in August 2014, I visited Ponsot at his winery in the sleepy town of Morey-Saint-Denis. Shaking my hand at the door, he introduced himself as the head of the French bureau of the FBI. "That stands for Fake Bottle Investigation," he said. Inside, we tasted Ponsot's 2013 vintage. "When I saw a 1929 in the catalog, I knew it was fake," he told me. "My grandfather didn't start estate bottling until 1934." Also on offer at the Cru auction were assorted vintages from '45 to '71—all fake.

Last spring I visited Morey- Saint-Denis again and tasted the 2015, which is already heralded as a landmark. Ponsot, whose demeanor is at times professorial and at others more like that of a secret agent, told me about the Grand Cru vineyards he has added to his portfolio via lease arrangements. (He would not divulge the names of the vine- yard owners.) He now makes 12 Grand Crus—the highest classification in Burgundy— more than any other domain.

He is definitely a maverick. Although Domaine Ponsot dates back to 1872, his winery is thoroughly modern. "I hate the word tradition," he says, "and I don't like old things." Except barrels, apparently: The winery's oak fermentation vats are 150 to 200 years old. Ponsot is almost unique in eschewing new barrels, which can impart tastes like vanilla. Such wines he calls "beverages."

Paradoxically, he is also among the most non- interventionist of winemakers, refusing to add sulfur, an almost universal protection against spoilage. "Why would you take aspirin if you don't have a headache?" he says. "I only treat a barrel if it develops a problem." He also rejects the use of cork, which, as every seasoned wine lover knows, often lets in too much oxygen—or, worse, trichloroanisole, a compound that results in a stinky wet cardboard taint when present in high quantities. (In my experience, trichloroanisole affects more than 5 percent of bottles.) After suffering a particularly high rate of cork taint in the late '90s, Ponsot set out to find a solution.

"I tested more than 4,000 bottles," he told me. (Not his own wine initially—too valuable.) The result, a new enclosure called Ardea Seal, is made of three poly- mers, including one used in artificial hearts, and has a corklike feel and permeability but controls the flow of oxygen. He began bottling his wines with it in 2008; others have been slow to follow. "The problem," he says, "is it's not traditional." He picks up one of the white stoppers, holds it out, and winks. "That and the fact that it looks like a suppository."

Such innovations sometimes seem to annoy his peers, possibly because of the media attention he receives, including his role in the upcoming documentary Sour Grapes, about the Kurniawan scandal. (The movie is to be released this fall.) Although it's been almost a decade since Kurniawan was exposed, Ponsot hasn't given up his investigation. I was astonished when he told me he'd gone to Indonesia and found Kurniawan's parents. He told me that a woman living in Kurniawan's house in Arcadia, California, whom Kurniawan identified as his mother, was also a fraud. "He did not act alone," Ponsot explained. However, when I pressed him for details, he turned reticent, becoming 007 again. "It will all be in my book," he said. Which I will wait for while contenting myself with his wines, some of the purest and most delicious in all of Burgundy.