Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

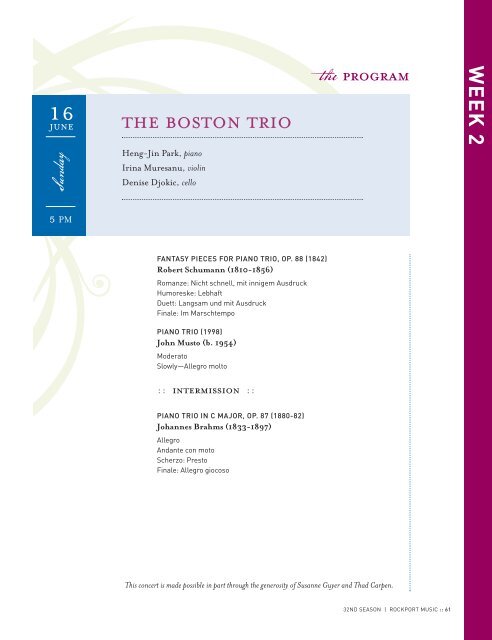

16junethe boston triothe programWEEK 2SundayHeng-Jin Park, pianoIrina Muresanu, violinDenise Djokic, cello5 PMFANTASY PIECES FOR PIANO TRIO, OP. 88 (1842)Robert Schumann (1810-1856)Romanze: Nicht schnell, mit innigem AusdruckHumoreske: LebhaftDuett: Langsam und mit AusdruckFinale: Im MarschtempoPIANO TRIO (1998)John Musto (b. 1954)ModeratoSlowly—Allegro molto:: intermission ::PIANO TRIO IN C MAJOR, OP. 87 (1880-82)Johannes Brahms (1833-1897)AllegroAndante con motoScherzo: PrestoFinale: Allegro giocosoThis concert is made possible in part through the generosity of Susanne Guyer and Thad Carpen.32ND SEASON | ROCKPORT MUSIC :: 61

<strong>Notes</strong>on theprogrambySandra HyslopFANTASY PIECES FOR PIANO TRIO, OP. 88Robert Schumann (b. Zwickau, June 8, 1810; d. Endenich, July 29, 1856)Composed 1842; 19 minutesFrom beginning to end, Robert Schumann carved his professional music path through resistantterritory. Growing up in a literary household, he was surrounded by books—his fatherwas a literary scholar and a book collector—and young Robert realized his first creative impulsesin the world of letters. Drawn particularly to lyric poetry, he organized a literary clubwith his teenage friends. In his mid-20s and into his 30s he was the editor of, and wroteextensively for, the music journal Neue Zeitschrift für die Musik [New Journal of <strong>Music</strong>].Having had some piano lessons, Schumann was unhappily engaged in law studies at theUniversity of Heidelberg when he begged his widowed mother’s approval of a bold plan: ifhis piano professor Friedrich Wieck would consent, Robert Schumann proposed to becomea concert artist and perhaps, even, a composer.The next segment of Schumann’s rocky path is well-known: how heleft Heidelberg, studied with Professor Wieck, fell in love with his pianoteacher’s talented daughter, permanently injured his hand, and won thelove of Clara Wieck, who became his muse and wife for the remainderof his short life. For Clara he wrote most of his extensive body of pianoworks—solo pieces and a concerto, as well as chamber music anddozens of magnificent songs for voice and piano. Despite his late start,Schumann’s ambitions were ultimately successful, thanks to doggeddetermination and his impeccable, intuitive taste in music and itsaesthetics.Clara Schumann and Josef Joachim frequently played RobertSchumann’s compositions.“Titles for pieces of music…have beencensured here and there, and it hasbeen said that ‘good music needs nosignpost.’ Certainly not, but neitherdoes a title rob it of its values; and thecomposer, in adding one, at least preventsa complete misunderstanding ofthe character of his music. If the poetis licensed to explain the whole meaningof his poem by its title, why maynot the composer do likewise? What isimportant is that such a verbal headingshould be significant and apt. It maybe considered the test of the generallevel of the composer’s education.”–Robert SchumannSchumann tended to compose in waves, concentrating largely on onegenre at a time. First, the piano phase, when he composed most of hisimportant works for the instrument. During the year 1840 alone, inthe euphoria of his passion for Clara—and combining his love for lyricpoetry with his newfound skill as composer for piano—he wrote 168Lieder, solo songs with piano accompaniment. In the year followingtheir marriage, when Clara’s career as a concert pianist kept her awayfrom home, Schumann undertook a private study of the great works ofchamber music, especially the string quartets of Mozart and Beethoven.Once again, in one year, 1842, he turned out a remarkable body of work:three string quartets, a piano quartet, a piano quintet, and this piano trio.The piano trio lay on the shelf for several years. In 1849 Schumanntook it out for revision and in 1850 published it with the title Phantasiestücke[Fantasy Pieces]. Although these pieces do not have a specificliterary component, they would not exist without Schumann’s passionfor German lyric poetry. The aesthetics of the poet and philosopherNovalis (G. P. F. von Herdenberg, 1772-1801) were particularly influentialon Schumann’s approach to the structures and affects of music. ThePhantasiestücke suite exemplifies what would come to be regarded asthe essence of the German Romantic approach to composition—62 :: NOTES ON THE PROGRAM

striving for expression beyond formal structures, reverence for nature and its mysteries,and the power of language and letters to shape music.PIANO TRIOJohn Musto (b. Brooklyn, 1954)Composed 1998; 15 minutesJohn Musto’s Piano Trio was commissioned by George Steel of the Miller Theater atColumbia University for the Ahn Trio, which premiered the work on October 13, 1998. Byturns lyrical and vivacious, driving and bluesy, the Piano Trio reveals Musto’s principalinspirations as a composer: piano and voice.A photo of Johannes Brahmsin 1886, not long afterthe composition of theC major Piano TrioThat there is no singer in this work does not negate its innate lyricism and melodicinventiveness. Musto has written of the Piano Trio: “The tunes in the piece grew out ofimprovisations at the keyboard. It is cast in two movements: moderate and slow/fast.In the first movement, a songful beginning gives way to a more vigorous contrapuntalexchange, and a final burst of energy in the coda. The second movement alternates a slow,nighttime-in-the-city blues with a frenetic bop section. The lyrical strains of the first movementbriefly try to re-emerge, but are swept aside by a violent coda.” The Piano Trio’s firstmovement, Moderato, is driving and vivacious; the second movement provides a lyricalinterlude; the Trio ends with a brilliant and jazzy flourish.Musto’s dual career as a successful composer and pianist has emerged naturally from histraining with the eminent American pianists Seymour Lipkin and Paul Jacobs. He has saidthat he “learned to write music by playing it.” Now noted for his several operas, works forvoice and orchestra, and many songs—often written with his wife, the soprano Amy Burton,in mind—Musto has achieved prominence in the vocal field while continuing to write forinstruments as well. Two piano concertos, several chamber works (including a stringquartet), and two pieces for large orchestra are currently on his works list with his publisherPeermusic. His music has been widely recorded on CD. Musto is a frequent guest lecturerat The Juilliard School, Manhattan School of <strong>Music</strong>, and other colleges and conservatoriesof music.PIANO TRIO IN C MAJOR, OP. 87Johannes Brahms (b. Hamburg, May 7, 1833; d. Vienna, April 3, 1897)Composed 1880-1882; 19 minutesIn 1854 Johannes Brahms composed his first Piano Trio, one of his earliest published works.It eventually met the fate of many of Brahms’s compositions: major revision. Holding himselfto the highest standards, the composer returned to the work many years later, writing to hisclose musical confidante Clara Schumann, “I have re-written my B-major trio…it will not beso muddled up, but will it be better?”Brahms felt no such doubts about his second Piano Trio. “You have never before had such abeautiful work from me and very probably have not published one to match it in the last tenyears,” Brahms wrote to his publisher, Fritz Simrock, in 1882. Even to Clara Schumann he:: 63

<strong>Notes</strong>on theprogrambySandra Hyslopreferred to his new C major Piano Trio as “one of my finest works.” Coming from Brahms,who had become notorious for his exceeding self-criticism, these expressions of confidenceare as startling as they were rare.In summer 1880 Brahms had begun composing the C major Piano Trio in Bad Ischlduring his annual working vacation. Putting it aside while he completed other major works,he finished it in August 1882 and performed it privately for friends in Bad Ischl. Simrockpublished the Trio later that year as Opus 87. Its first public performance took place inFrankfurt-am-Main on December 29, 1882. Brahms himself was at the piano, with colleaguesFriedrich Hermann, violin, and Wilhelm Müller, cello.The Piano Trio in C major is justly noted not only for its beauties, apparent already on a firsthearing, but also for its masterful construction. The grand first movement opens with theviolin and cello playing an expansive main theme in unison. The piano contributes a stepwisesecondary theme, and the strings join in for a third principal melody. Brahms worksthese themes into a concise sonata form, with the strings frequently playing together asa complement to the strength of the piano. The movement ends with an extended coda.For the second movement, predominately in A minor, Brahms chooses one of his favoritestructures, a theme and variations. This is one of his most sophisticated and successful inthat form. The strings play the melancholy main theme, which has the character of anEastern European folk song, while the piano plays offbeat accompanying chords. In the fivevariations Brahms alternates between working with the strings’ initial melody and developingthe offbeat piano accompaniment.The scampering main themes of the Scherzo, in C minor, demand technical fluency from allthree instruments and from the ensemble, which must maintain crisp delicacy in the outerportions of the movement. The inner Trio creates gentle repose, with a burst of sunny optimismfrom the piano, before returning to the scampering conclusion. The Scherzo endswith a C major whisk that predicts the return of the tonic key in the final movement.The Finale, Allegro giocoso, turns the scampering of the Scherzo into an all-out instrumentalrace of good-humored themes. But for a short contemplative oasis toward the conclusion,the Finale is a flashy display of virtuosity.64 :: NOTES ON THE PROGRAM