2018 School Spending Survey Report

Laurie Halse Anderson Reflects on the "Seeds of America" Trilogy

Pat Scales speaks with the prolific author about conducting historical research, creating authentic voices, and approaching our nation's history with honesty.

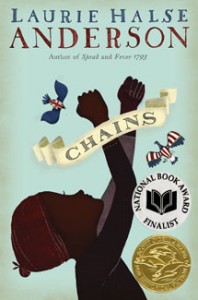

Ashes (Atheneum/Caitlyn Dlouhy Bks., Oct. 2016) is the third title and conclusion to Laurie Halse Anderson’s historical “Seeds of America” trilogy. The stories take place as the nation fights for its freedom from England, and Isabel, Ruth, and Curzon, who have only known life in bondage, begin a perilous struggle for their own freedom. Their journey takes them from Rhode Island to New York City (Chains; S. & S./Atheneum, Oct. 2008); Valley Forge, PA, to Saratoga, NY (Forge; S. & S./Atheneum, Oct. 2010); and Charleston, SC, to Williamsburg, VA (Ashes; Atheneum/Caitlyn Dlouhy Bks., Oct. 2016). Along the way, they are separated and reunited, and the harsh cruelties of war take a toll on their relationship. In the final days of their struggle, they come to realize that they must rely on one another if they are to survive. You write historical and contemporary fiction. How is the writing process different? My contemporary YA novels start with a topic that gnaws at me, like teens whose parents have PTSD (The Impossible Knife of Memory; Penguin, Jan. 2014) or eating disorders (Wintergirls; Viking, Mar. 2009). I’ll research the idea, interview people, and ponder the topic for a while, sometimes for years. Eventually, characters emerge out of my subconscious and start whispering in my left ear. That’s when I start to write. My historical novels are written from the other direction, starting in plot instead of character. First I identify the historical events into which I want to insert my characters. Once I have a deep understanding of those events, I develop lists of how my characters could interact with that world. Finally, I sit down and untangle the knots of my characters’ inner lives in order to figure out their motivations and internal arcs, and how they intersect with the lives of the other fictional characters as well as the factual historic events. And then I wait to hear the whisper of a character in my left ear.

Ashes (Atheneum/Caitlyn Dlouhy Bks., Oct. 2016) is the third title and conclusion to Laurie Halse Anderson’s historical “Seeds of America” trilogy. The stories take place as the nation fights for its freedom from England, and Isabel, Ruth, and Curzon, who have only known life in bondage, begin a perilous struggle for their own freedom. Their journey takes them from Rhode Island to New York City (Chains; S. & S./Atheneum, Oct. 2008); Valley Forge, PA, to Saratoga, NY (Forge; S. & S./Atheneum, Oct. 2010); and Charleston, SC, to Williamsburg, VA (Ashes; Atheneum/Caitlyn Dlouhy Bks., Oct. 2016). Along the way, they are separated and reunited, and the harsh cruelties of war take a toll on their relationship. In the final days of their struggle, they come to realize that they must rely on one another if they are to survive. You write historical and contemporary fiction. How is the writing process different? My contemporary YA novels start with a topic that gnaws at me, like teens whose parents have PTSD (The Impossible Knife of Memory; Penguin, Jan. 2014) or eating disorders (Wintergirls; Viking, Mar. 2009). I’ll research the idea, interview people, and ponder the topic for a while, sometimes for years. Eventually, characters emerge out of my subconscious and start whispering in my left ear. That’s when I start to write. My historical novels are written from the other direction, starting in plot instead of character. First I identify the historical events into which I want to insert my characters. Once I have a deep understanding of those events, I develop lists of how my characters could interact with that world. Finally, I sit down and untangle the knots of my characters’ inner lives in order to figure out their motivations and internal arcs, and how they intersect with the lives of the other fictional characters as well as the factual historic events. And then I wait to hear the whisper of a character in my left ear.  Explain how you approached the research for the “Seeds of America” series. How long did the research take? When did you know the research was complete? I research as if I’m preparing to write a dissertation instead of a novel. This has a lot to do why the trilogy has taken 12 years to research and write. I started to read about the Colonial and Revolutionary eras back in 1993, when I began work on Fever 1793 (S. & S., Sept. 2000). So by the time I hit upon the idea for Chains, I had a decent background in the politics and general events of the period. Here’s an example of my process: my research starts with general topics, such as—for Ashes— “The American Revolution in the South.” I studied the battles, especially the siege of Charleston and what happened when the city fell to the British. I read all of the primary source material from Virginia, the Carolinas, and Georgia I could find. At first I considered setting some of the action in Georgia, because it is so rarely talked about, but I ruled it out in favor of Charleston. I spent a week at the South Carolina Historical Society, only to discover on my last day there some facts about the registration of enslaved people in Charleston in 1781 that completely sunk my plot for the first half of the book. Much of Ashes wound up taking place in Williamsburg, VA, as the American and French armies gathered there, and then to the siege of Yorktown, covering from September to early November of 1781. To understand what was going on in the region during those weeks, I had to study what had taken place earlier in the year, because the British had occupied Williamsburg, and British forces led by Benedict Arnold burned a swath through Virginia. All of this impacted the lives of young people looking for work, like Isabel, Curzon, and Ruth. The fact that so many enslaved Virginians took advantage of the chaos and ran for their freedom also had a huge impact on my characters. I dug deep for details such as the food served in taverns, the way clothes were washed, the numbers of African American soldiers at Yorktown, what cannon and mortar fire looked like at night, the bodies of dead horses in the river, how the soldiers dug trenches, the swamp water that tasted of frog, and thousands of other details. I read every single scrap of paper written in the time period about the events there, as well as the many academic papers and books that have been written about it in the past two generations.

Explain how you approached the research for the “Seeds of America” series. How long did the research take? When did you know the research was complete? I research as if I’m preparing to write a dissertation instead of a novel. This has a lot to do why the trilogy has taken 12 years to research and write. I started to read about the Colonial and Revolutionary eras back in 1993, when I began work on Fever 1793 (S. & S., Sept. 2000). So by the time I hit upon the idea for Chains, I had a decent background in the politics and general events of the period. Here’s an example of my process: my research starts with general topics, such as—for Ashes— “The American Revolution in the South.” I studied the battles, especially the siege of Charleston and what happened when the city fell to the British. I read all of the primary source material from Virginia, the Carolinas, and Georgia I could find. At first I considered setting some of the action in Georgia, because it is so rarely talked about, but I ruled it out in favor of Charleston. I spent a week at the South Carolina Historical Society, only to discover on my last day there some facts about the registration of enslaved people in Charleston in 1781 that completely sunk my plot for the first half of the book. Much of Ashes wound up taking place in Williamsburg, VA, as the American and French armies gathered there, and then to the siege of Yorktown, covering from September to early November of 1781. To understand what was going on in the region during those weeks, I had to study what had taken place earlier in the year, because the British had occupied Williamsburg, and British forces led by Benedict Arnold burned a swath through Virginia. All of this impacted the lives of young people looking for work, like Isabel, Curzon, and Ruth. The fact that so many enslaved Virginians took advantage of the chaos and ran for their freedom also had a huge impact on my characters. I dug deep for details such as the food served in taverns, the way clothes were washed, the numbers of African American soldiers at Yorktown, what cannon and mortar fire looked like at night, the bodies of dead horses in the river, how the soldiers dug trenches, the swamp water that tasted of frog, and thousands of other details. I read every single scrap of paper written in the time period about the events there, as well as the many academic papers and books that have been written about it in the past two generations.  Simon and Schuster offers an interactive map that traces Isabel and Curzon’s footsteps. Did you visit the historic places mentioned in the book, or did you follow the footsteps of your characters through books that you read? Google Earth can be a useful tool, but it’s not a substitute for walking the paths that your characters walk. Visiting South Carolina plantations in August, walking the battlefields of Saratoga, the streets of Charleston, Valley Forge National Park, Colonial Williamsburg, Yorktown, and the tip of Manhattan helped me make sense of the 18th-century source materials I was reading. I used maps that were created in the time period, supplemented by street directories, merchant addresses found in newspapers, tax rolls, and drawings. I also attended many American Revolution reenactments to watch and learn how the stuff of daily living was done: rolling gunpowder cartridges, drilling with muskets, digging cook fires, stitching up battle wounds, making candles and soap, etc. Interaction between fictional characters and real characters is an important characteristic of excellent historical fiction, and you do it seamlessly. At what point in your research did the fictional characters begin to take shape? Weaving of fictional characters on to a realistic historic tapestry is a huge challenge, but a fun one. Once I understand where and when my characters need to be—Isabel negotiating the perils of New York right after the British invasion in Chains, Curzon and his friends enduring the starving times at Valley Forge in Forge, and both of them trying to survive the Siege of Yorktown in Ashes—I look for the small scenes of ordinary life. In Ashes, for example, Isabel and Ruth are walking the encampment of the French and American armies, hungry and in search of work. They are also eager to avoid the cannonballs being lobbed at them by the British. Once I begin to visualize the smallest details—the smell of pines being cut down for trench construction, the sight of a wounded soldier being rushed to the hospital tent by his friends, the sounds of frightened horses and yelling sergeants—then I can hear my characters’ thoughts and words. Chains is really Isabel’s story, and Forge Is Curzon’s story. Tell us about the decision to make Ashes Isabel and Curzon’s story. My original thought was to tell the story from alternating points of view, jumping between Curzon and Isabel. But when I ran that idea past my readers, they wrinkled their noses. It would be fun to experiment with a shorter middle grade novel that is framed with distinct narrators, but I felt that to do so in Ashes would have been asking too much for readers of a book that is already densely layered with historical details and slightly challenging language.

Simon and Schuster offers an interactive map that traces Isabel and Curzon’s footsteps. Did you visit the historic places mentioned in the book, or did you follow the footsteps of your characters through books that you read? Google Earth can be a useful tool, but it’s not a substitute for walking the paths that your characters walk. Visiting South Carolina plantations in August, walking the battlefields of Saratoga, the streets of Charleston, Valley Forge National Park, Colonial Williamsburg, Yorktown, and the tip of Manhattan helped me make sense of the 18th-century source materials I was reading. I used maps that were created in the time period, supplemented by street directories, merchant addresses found in newspapers, tax rolls, and drawings. I also attended many American Revolution reenactments to watch and learn how the stuff of daily living was done: rolling gunpowder cartridges, drilling with muskets, digging cook fires, stitching up battle wounds, making candles and soap, etc. Interaction between fictional characters and real characters is an important characteristic of excellent historical fiction, and you do it seamlessly. At what point in your research did the fictional characters begin to take shape? Weaving of fictional characters on to a realistic historic tapestry is a huge challenge, but a fun one. Once I understand where and when my characters need to be—Isabel negotiating the perils of New York right after the British invasion in Chains, Curzon and his friends enduring the starving times at Valley Forge in Forge, and both of them trying to survive the Siege of Yorktown in Ashes—I look for the small scenes of ordinary life. In Ashes, for example, Isabel and Ruth are walking the encampment of the French and American armies, hungry and in search of work. They are also eager to avoid the cannonballs being lobbed at them by the British. Once I begin to visualize the smallest details—the smell of pines being cut down for trench construction, the sight of a wounded soldier being rushed to the hospital tent by his friends, the sounds of frightened horses and yelling sergeants—then I can hear my characters’ thoughts and words. Chains is really Isabel’s story, and Forge Is Curzon’s story. Tell us about the decision to make Ashes Isabel and Curzon’s story. My original thought was to tell the story from alternating points of view, jumping between Curzon and Isabel. But when I ran that idea past my readers, they wrinkled their noses. It would be fun to experiment with a shorter middle grade novel that is framed with distinct narrators, but I felt that to do so in Ashes would have been asking too much for readers of a book that is already densely layered with historical details and slightly challenging language.  The novels are written in first person. What is the most challenging thing about capturing an authentic voice in historical fiction? Humility and respect are necessary when writing outside your own experience. Writing characters unlike you in the first person point-of-view requires an even deeper understanding of perspective; how does that character see the world? When writing about a character in 2016, I could have her describe the color orange as the color of a basketball or a school bus. That obviously doesn’t work for a character living in 1781. Isabel describes the oppressive heat of a Carolina swamp by saying, “The air clung to our throats like hot wax…” She says the waning moon “shrank as if it were being whittled away by a sharp paring knife.” Deeply immersed in war itself, she uses military terms to describe ordinary things such as the “battalions of troublesome insects” that stung and tormented them on their journey. One of the things to keep a sharp eye out for in the last stage of revision is to make sure that the narrator’s voice is consistent, and that the author’s voice has not crept in. Did you know the ending of each book when you began the writing? Yes, but I had no clue how I was going to get there. Hence, the adventure of writing! The three books were published over the span of eight years. How did you manage to maintain the continuity of story over this time frame? Carefully detailed plot outlines, a robust system of note taking, and never throwing away any research certainly helped. Sometimes I had to go back and explain something from an earlier book, but write it in such a way that a reader who only read that single book of the trilogy would not be confused. For example, I pulled the name “Curzon” out the air when I wrote Chains. But names were incredibly significant to enslaved people because so many of them were burdened with a name imposed on them by those who held them in bondage. So when writing Forge, I created a backstory to Curzon’s name that shows the reader (and Isabel) a new side to him and helps create a very tender scene between the two of them. One of the challenges of Ashes was understanding that Isabel, Curzon, and Ruth are all six years older than when we first met them, and that the experiences of those six years has shaped each of their characters. That took quite a bit of pondering and many discarded scenes to figure out. The titles in the series are evocative and effective. Do titles come to you before or during the writing process? I used Chains because so many political arguments of the day talked about America being bound in chains of oppression. At the same time, the wealthiest Americans were buying and selling people bound in actual chains. Forge was an obvious choice because the book is largely set at the famous winter encampment at Valley Forge. When I learned how black Americans—free, enslaved, or self-liberated—were treated at the end of the Revolution, I hit upon Ashes. The Declaration of Independence spun grand dreams of the way people would be treated in the United States. The ravages of eight years of war and the struggle to create a shared nationhood left many of those dreams in ashes, particularly for people of color. Why is it so important to approach our nation’s history with honesty? So many of the problems we deal with in the United States today—racism, injustice, disparities in education, economic opportunity, access to clean water and air, to name a few—stem from the choices made in the late 1700s by wealthy white men. They chose to build a nation on the backs of enslaved families. They fought a war for the lofty ideals promised in the inspirational language of the Declaration of Independence, but failed to live up to them. Once all Americans acknowledge and understand this history, we can get to work on building the nation that we promised ourselves.

The novels are written in first person. What is the most challenging thing about capturing an authentic voice in historical fiction? Humility and respect are necessary when writing outside your own experience. Writing characters unlike you in the first person point-of-view requires an even deeper understanding of perspective; how does that character see the world? When writing about a character in 2016, I could have her describe the color orange as the color of a basketball or a school bus. That obviously doesn’t work for a character living in 1781. Isabel describes the oppressive heat of a Carolina swamp by saying, “The air clung to our throats like hot wax…” She says the waning moon “shrank as if it were being whittled away by a sharp paring knife.” Deeply immersed in war itself, she uses military terms to describe ordinary things such as the “battalions of troublesome insects” that stung and tormented them on their journey. One of the things to keep a sharp eye out for in the last stage of revision is to make sure that the narrator’s voice is consistent, and that the author’s voice has not crept in. Did you know the ending of each book when you began the writing? Yes, but I had no clue how I was going to get there. Hence, the adventure of writing! The three books were published over the span of eight years. How did you manage to maintain the continuity of story over this time frame? Carefully detailed plot outlines, a robust system of note taking, and never throwing away any research certainly helped. Sometimes I had to go back and explain something from an earlier book, but write it in such a way that a reader who only read that single book of the trilogy would not be confused. For example, I pulled the name “Curzon” out the air when I wrote Chains. But names were incredibly significant to enslaved people because so many of them were burdened with a name imposed on them by those who held them in bondage. So when writing Forge, I created a backstory to Curzon’s name that shows the reader (and Isabel) a new side to him and helps create a very tender scene between the two of them. One of the challenges of Ashes was understanding that Isabel, Curzon, and Ruth are all six years older than when we first met them, and that the experiences of those six years has shaped each of their characters. That took quite a bit of pondering and many discarded scenes to figure out. The titles in the series are evocative and effective. Do titles come to you before or during the writing process? I used Chains because so many political arguments of the day talked about America being bound in chains of oppression. At the same time, the wealthiest Americans were buying and selling people bound in actual chains. Forge was an obvious choice because the book is largely set at the famous winter encampment at Valley Forge. When I learned how black Americans—free, enslaved, or self-liberated—were treated at the end of the Revolution, I hit upon Ashes. The Declaration of Independence spun grand dreams of the way people would be treated in the United States. The ravages of eight years of war and the struggle to create a shared nationhood left many of those dreams in ashes, particularly for people of color. Why is it so important to approach our nation’s history with honesty? So many of the problems we deal with in the United States today—racism, injustice, disparities in education, economic opportunity, access to clean water and air, to name a few—stem from the choices made in the late 1700s by wealthy white men. They chose to build a nation on the backs of enslaved families. They fought a war for the lofty ideals promised in the inspirational language of the Declaration of Independence, but failed to live up to them. Once all Americans acknowledge and understand this history, we can get to work on building the nation that we promised ourselves.

RECOMMENDED

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!